My father owned a 1938 Willys. He bought it used. It was gray, and kind of ugly.

In fact, it was downright ugly.

It looked something like the car in this photo.

My father, C. H. (Brick) Garrigues, and my stepmother, Naomi Silver, called their Willys “Ducksy.” It was a girl car; it was a “she.”

I think drivers named their cars in those days as kind of a talisman. You had to pat your car on the dashboard and say, “Come on, Ducksy,” from time to time, to make sure the little guy (or girl) would get you where you wanted to go.

But the car had guts. No wonder that beginning in 1941 Willys turned out thousands of Jeeps for the war effort. And you know how well those babies performed!

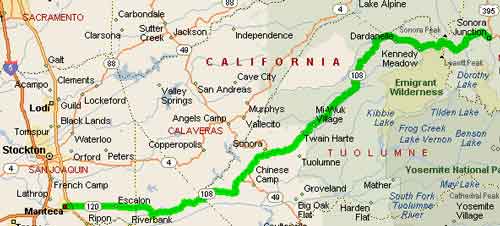

In August 1941, Brick was taking a well-deserved break with Naomi from his job on the copy desk of the San Francisco Examiner. They went camping in the Stanislaus National Forest.

This is what he wrote:

It was a swell vacation trip. We took a sleeping bag and a few utensils and a little food. When night came we’d find a quiet place a few miles off the road and cook our dinner beside a brook, then curl up and go to sleep. Always we were above five thousand feet and three nights above seven thousand.

One night, up eight thousand, we got caught in a terrific thunderstorm and had to take a cabin at a little resort. But it was magnificent.

Imagine yourself up eight thousand feet on the mountain edge of the desert, in a cul-de-sac surrounded by peaks from eleven thousand to thirteen thousand feet high and the loop of the peaks enclosing terrace of lake after lake — melting snow pouring over the cliffs in waterfalls and cascades, forming an intensely blue lake miles around and then plunging down the next terrace to the next lake — all surrounded by dark firs and pines with deep red bark.

Behind the peaks, huge, dark thunderclouds with lightning shooting from peak to peak —

Coming back we decided to try and take the little Willys across Sonora Pass, which is the worst of the passes over the Sierra.

From the valley floor at six thousand you climb to seven thousand up the bank of a tumbling river which pours down from the glaciers. Then the road sign says: Steep grade ahead, and you shove it into low and give it the gun, winding up and up the bare side of a huge glacial moraine.

The storm is still thundering; you climb fifteen hundred feet almost straight up, and the rain gets heavier and heavier. You come out in the pass itself, stunted, wind-whipped trees, gnarled rocks and the river gnashing itself against the fantastic stones. Two huge peaks on either side: the lightning smashes at one and then the other, and the rain beats down so heavily on the tin top of your car that you can scarcely tell the sound from the thunder.

The car digs in and pulls as you go up and up, swinging around curves, until finally she straightens out and you seem to be pointing the nose of the car straight at the sky for the last two hundred yards. The car groans — and starts to take it and finally — just a dozen feet from the summit — she dies.

There’s a terrific clap of thunder and the rain changes to hail — and there you are — a dozen feet from the top in one direction and two hundred miles from any other pass.

You try again and she moves forward six inches; you try it again and get a foot; you try it again and again, and in a dozen tries you’re over. But the rain is coming down so you can’t see the road; the lightning is still crackling around your head and you’d give anything to get out of there.

You put her into low gear and creep down with your foot jammed on the brake. The rain has loosened some stones, and they rattle down on top of your car. You’d give anything to be able to go down at more than five miles an hour.

As you round a turn, you see that the rainwater is pouring in a cataract five hundred feet high into the top of a small snow field on the perpendicular mountain and you wonder if the flow will loosen the hundred acres of snow and start an avalanche.

You try to keep from going any faster, and finally you get down below the rain, and people are having a picnic in a meadow, and you realize for the first time how scared you really were.

It probably wasn’t actually dangerous; I’ll never know. But for sheer dramatics (especially the thunderclap and the hail just as the engine died), it was quite enough for me. Ten years later, they sold that car and bought a Nash. You could fold back the two front seats and make a bed in it. And it had LOTS more power.

| A 1938 Willys like Ducksy, whose little engine conquered the Sonora Pass |

|

| Return to the story |

| A 1951 Nash; you could make a bed in it |

|

•