In casual conversation when I was a child, I learned that my father quit the football squad at Imperial High School because one of his best friends had been killed in a game (it was a rough sport then, with little in the way of protective gear).

I forgot about it until I visited Imperial High School in Imperial, California, to do research on my book about my faher and I saw an ancient plaque paying tribute to “Ephraim Grant Angell,” who had died in a football game on November 21, 1916.

It was almost a physical shock when I realized that a distant, shadowy, casually mentioned event had suddenly become real in the form of a name etched in metal on a high school wall.

And I knew, too, that my father had paid his respects to his friend and teammate, young Angell, by using him as a character in his novel, not as a football player but as a runner.

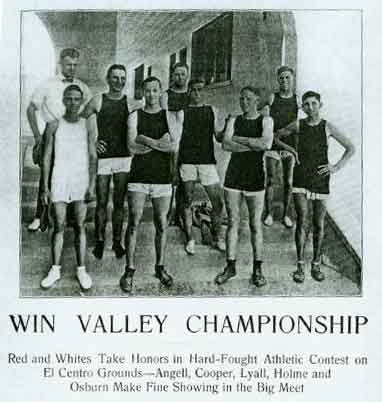

| These are the boys Brick Garrigues thought about when he wrote Many a Glorious Morning — From Oasis, the Imperial High School yearbook |

|

By C. H. Garrigues

Dick was a little guy with blond hair and blue eyes and a baby face. They called him Angel, not Angell, because he looked like one. He went out for everything and didn’t make any teams except the track team, where Coach Clark let him run the mile because they needed some milers.

The mile was the last event, and El Jardin was behind Bostonia, so that if Angel could win five points for first it meant victory in the meet. They were ten points ahead of Hillside. If Hillside’s miler took first place and El Jardin second and Bostonia third, it still meant victory.

But everybody knew that Dick Angell couldn’t possibly place better than third, and by the time the race started everybody was getting ready to go home because it didn’t seem worthwhile to stay and watch the slaughter.

But then somebody let out a yell, and those who were leaving turned to look. Bostonia’s lone entry had pulled a tendon on the first turn and dropped out.

His coach yelled at him to stay in and hobble around because he might get the one point which they’d need to win, but once you’re out of the lanes you can’t go back; the El Jardin rooters took heart and started yelling, “Go it, Dick! Go it, kid!” and Dick Angell looked around, saw what happened and tried to stretch out his short legs into the miler’s stride.

Near the end of the half he threw a shoe. They weren’t running on cinders; they were running on dirt, and his spiked shoe caught in a lump of clay and went sailing over his head into the infield He hesitated a second as though to retrieve it, then realized he couldn’t and kept on running with just one shoe.

The kids knew what it was to try to walk across a field with bare tender feet; they knew how it was when you started out barefoot in summer after a winter of wearing shoes. They started to yell and the noise grew; Dick dug in and kept going — by the time he came around in front of the bleachers again, his sock was torn off, and his foot was raw and bleeding, and Coach Clark sent in Neil Wiley, the track captain, to pull him out.

Neil ran alongside him for a while and then dropped out and shook his head at the coach, and Clark dashed across the infield and tried to stop Angell; he started to move right in and pick him up and carry him off the track, but at the look on Dick’s face the coach, too, stopped and he called to Wiley, “Pace him in, kid.”

So Wiley dropped in beside Angel, running in the infield but close enough so Angel could watch his feet and guide his own pace with them and know that he was not alone but that all he had to do was keep putting one foot in front of another and he would get there.

Wiley said afterward that he could hardly stand it; Dick’s foot was like a big chunk of raw hamburger that left a gob of blood every time he put it down.

The crowd was screaming; half, mostly the girls, were calling for the coach to go out and stop it, and the other half, mostly the boys, were yelling for Dick to win. And the strange part was that he was winning, not first, of course, because the Hillside man came in with first place, but second, which was what El Jardin had to have to win the meet.

Somehow he kept ahead of the man from San Benito, who was the only other one left in the race, and when little Dick Angell ran across the finish line and into Coach Clark’s arms, El Jardin had won another championship.

Nobody had cried when they lost the football championship to Bostonia. But most of the girls, and, yes, even some of the boys, were crying when they carried Dick Angell off the track and down to the hospital. They followed the car in which Coach Clark was holding Angel on his lap, and they cheered and let the tears run down their faces unashamed.

Nobody saw Bliss Lane start for home, still wearing his track shorts, and turn off the road and go over behind the big Bull Durham sign and throw himself down in the dried weeds. He lay there for a long time, with his shoulders shaking and the tears running off his face and into the caked dirt.

After a long time the sun was setting and he felt cold; he got up and went home.

Nobody noticed the marks of tears on his face, and he never told anybody about that, not even Bob Reynolds. The nearest he ever came to it was once, when he said to Bob, “Sure, kid, did you ever notice how it’s the big shots that let the school down, and a little squirt like Angel comes along and really measures up?”

That was the way his athletic career ended.