My brother Chuck, at age sixteen, and my father, C.H. (Brick) Garrigues were carrying on what I call their “lifelong conversation.”

It must have begun with Brick dandling Chuck on his knee as a baby.

And it continued, even when Chuck and I were living in a small town just outside Los Angeles and Brick was with his second family in the San Francisco Bay area.

Never by phone, of course, because Brick had a horror of spending money on long-distance calls, which, to be honest, could have taken quite a chunk of a newspaperman’s salary in the postwar runaway inflation years. But they wrote frequently.

An example: this fragment of a letter from Chuck to Brick.

(Undated; probably 1946)

Dear Pop,

I was mowing the lawn yesterday, when all of a sudden I realized why grownups like Alice in Wonderland, while most kids dislike it intensely.

Kids have the ability to adapt themselves to new conditions without being particularly impressed by them. So, in Alice it is explained to the reader that time works backwards, and the queen first cries out, and then pricks her finger with a pin. The adult is delighted by this, but the child says, “All right, those conditions are taken into consideration, proceed with your anecdote.”

What do I think of the kind of people who enjoy Alice?

They are fascinated by situation — much as a child likes a bright colored object. Therefore, they aren’t very imaginative; something has got to be really unusual to make them react. Parenthetically, I liked Sylvie and Bruno better than Alice.

Love,

Charles

Sylvie and Bruno and Sylvie and Bruno Concluded by Lewis Carroll were published in 1889 and 1893. They featured chapters alternating between discussions of nineteenth-century ethical problems in England and the half-serious, half-comic adventures of a good monarch and his children in a mystic fairy-tale kingdom.

It is a very curious thing how much effect Chuck and Brick had upon each other. One expects the father to influence the son, but in our family the opposite was also true. Chuck’s teen-age enthusiasm for science-fiction, to give another example, had sparked a similar curiosity in Brick.

Chuck was, at the time, writing science-fiction short stories and sketching out plots. He had subscribed to the magazine Writer’s Digest. Chuck suggested that Brick read a book on writing by the caustic Jack Woodford (his real name was Jack Woolfolk; he was born in 1894 and died in 1971).

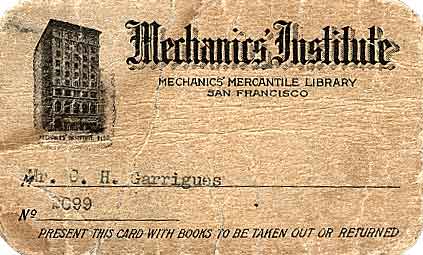

Brick found a copy of Woodford’s How to Write and Sell a Novel in the Mechanics’ Institute in downtown San Francisco.

June l0, l946

Hi,

Having got the Jack Woodford book out of the library, and

having read part of it I am now sufficiently discouraged with the story I was writing, so I guess I can take a morning off and write letters.

It was good to hear from you — at long last. I was really beginning to miss you on your birthday; and, as a matter of fact, I almost called up your Mom to congratulate her on the very splendid event. I guess it was because you’re sixteen; after that a fellow is more or less on his own — while his old man retires into innocuous decrepitude.

Still, I do think that by application of due diligence and fortitude you can manage to finish a letter occasionally. And if they are not enough, let me give you some Woodfordish suggestions on: “How to Get a Letter Finished in Ten Easy Steps.”

l. Address an envelope before you start to write.

2. Put a stamp on it.

3. Start the letter.

4. When interrupted, write “more” and put the letter in the envelope.

5. Take five steps to a mantel, desk-top or other place where it can be noticeably propped.

6. Keep reminding Mom to mail it for you each day until she does it.

By following the Garrigues technique you cannot fail to succeed.

The Jack Woodford book is a find — whether disastrous or not, I don’t know. My present feeling, after getting halfway through, is one of discouragement and distaste — much as I am amused and delighted with the book. And I’m inclined to think that his description of the process of writing — even to feeding the canary — is exactly accurate.

His book raises a point which every writer attempts to dodge but which, nevertheless, must be answered. Let me expand in a Socratic dialogue:

SOCRATES: So, you want to write, eh? But why?

PLUTO: Well, ah — you know — well, I think I want to be a writer.

SOCRATES: But why?

PLUTO: Well, writers get talked about, and everybody knows about them and they make a lot of money, if they’re good. And they are able to put over their ideas, and some of them, if they are good enough, gain lasting fame so that, hundreds of years from now, little children will be tortured by being compelled to read what they have written and write book reports upon it.

SOCRATES: In other words, you expect writing to bring you wealth, and notoriety and — perhaps — fame; is that right?

PLUTO: I suppose so.

SOCRATES: Very well, then; are you aware that writing may bring you one of these three things, that it might bring you two, but that it can hardly, under any circumstances, bring you all three.

PLUTO: No, I was not aware of that. That is, I had noticed that something of the sort did seem to occur but I did not know that it must —

SOCRATES: It is something that all mature writers are aware of. Therefore, you must decide, and tell me now, which of these three things you want. And when you have decided, you must determine to be satisfied with the one you have chosen.

If you choose fame or notoriety you must not complain if you and your children do not have enough to eat.

If you choose money, you must not complain at the fact that your mind comes to smell like a pigpen and that you are unwilling to look at yourself in the mirror when you go to shave.

So, then, which do you choose?

PLUTO: Before I answer that, Socrates, tell me why it is that I must choose either-or. Why cannot I choose to have both?

SOCRATES: It is because publishing has become a mass-production industry in precisely the same way as the production of bread or soap is a mass-production industry.

That means that only the most profitable enterprises can survive. That means not the best goods but the lowest quantity of goods that can be made acceptable to the largest number of people — the lowest common denominator.

PLUTO: But isn’t it true, Socrates, that some writers do achieve notoriety, and fame and money, all together?

SOCRATES: Perhaps one in a million does. Or, rather, one in about seventy-five million. But even for those, the principle still holds; they must still choose, at every step, whether they are writing for fame or for money.

PLUTO: Well, now, Socrates, I think you will agree that this has turned out to be a hell of a Socratic dialogue. In the Socratic dialogue (as you will agree if you have read your Plato), Socrates is supposed to ask all the questions and trick his young pupil into giving silly answers. But here I have been asking the questions and you have been giving the silly answers.

June l7, l946

What I’m sort of wondering about is how greatly your future education is going to interfere with your future writing. You’ll get acquainted with the classics. You’ll read great writing. You may even pick up an idea or two. And do you, thereafter, become increasingly handicapped as a money-writer? (That is at least half facetious.)

As for myself, my first trouble was that I began to come into contact with writing and writers at just about the time when the United States was becoming literarily self-conscious. There was Dreiser and Hemingway and Hecht and Cabell and Dos Passos — all geniuses.

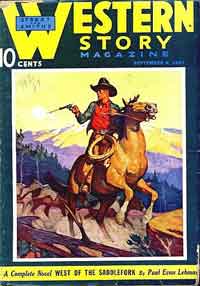

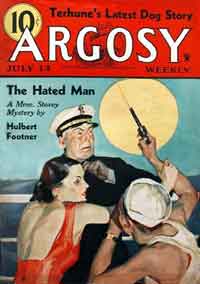

And it was, as my friend John Clayton says, a question of either being a genius or nothing. If I’d stuck to my Western Story and Argosy, I’d have probably been a money-writer twenty years ago. It’s only now that I’m getting over the effects.

I think one thing that has startled me since I’ve gone back to thinking in terms of fiction is the fact that, after having done reams and reams of reading in the

last twenty years, having become acquainted with the best in all literature, I suddenly discovered that I have added not one thing to my ability to write fiction. That discovery startled me. Woodford’s book drove it home.

I should be able to learn more quickly now than I could have learned at twenty-five. But the learning process has to be done all over.