Twenty-six-year-old Charles Harris (Brick) Garrigues, a reporter on the Los Angeles Illustrated Daily News, had been brought up in a farming family in California’s Imperial Valley near the Mexican border.

He had no musical training but his keen instincts led him to appreciate not only the popular music of his day but also the classics.

These letters to an old friend, Fanny Strassman, give a flavor of the musical tradition in a city that, in those long-ago days, was considered a cultural backwater.

|

January 24, l929 Dear Fanny, I haven’t been to but two concerts this winter. But one of them was Stokowski, directing the L.A. orchestra. Our orchestra is not bad, even though the director is terrible, and when Stokowski got through with two Bach Chorales and his Passacaglia the audience was ready to tear the seats up and use them to make loud and tumultuous noises with. Anyway, he got excited about the noise and the orchestra banging their instruments and proceeded to dash through the orchestra, shaking hands with everybody. I thought one old German, the leader of the basses, was going to kiss him smack flush square upon the mouth. There is a rumor, well-founded, I hope, that Los Angeles is going to hire him away from Philadelphia. Anyway, he’s bought a big home here. They’ll have to do something because the attendance at Schneevoigt’s concerts has dropped to about three old women with season passes. |

Georg Schneevoigt was music director of the Los Angeles Symphony from 1927 to 1929. He was succeeded by Artur Rodzinski, not by Stokowski.

By this time, Brick had married for three years to Beulah Dickey, a pretty young secretary he had met in Arizona and brought to live in a little house in Echo Park.

|

|

|

|

Sadakichi Hartmann

|

Isadora Duncan

|

|

February 20, l929 We’ve found the most bucolic place to live. It’s up in the hills north of Aimee’s temple. . . . [Man of letters] Sadakichi Hartmann’s most frequent Los Angeles stopping place is just at the top of the hill. I wish you could hear Sadakichi lecture on the dance. When I heard him he was recovering from one of his epileptic spells and was even more unintelligible than usual. But his gestures are enough to hypnotize you as he sways back and forth, illustrating what he has to say. He claims to have taught Isadora Duncan the things that really made her the dancer she was. After watching him for half an hour I haven’t the slightest doubt of it. . . . aged and sick and dissipated as he is, he’ll sometimes literally dance for hours for his own pleasure much as less strenuous persons would read a book. |

|

July 9, l929 I’ve appointed myself music critic, which doesn’t pay anything except by-lines and a chance to hear considerable music for nothing. Also I get an opportunity to pan some of my particular abominations such as Percy Grainger and [Eugene] Goossens. The latter is to conduct three weeks at the Bowl this summer, and I’m saving a whole dictionary full of vitriolic adjectives for his particular benefit. Also, I’ve been studying music, philosophy and history in order not to be too abysmally ignorant. |

|

|

|

|

Louise Caselotti and Maria Callas

|

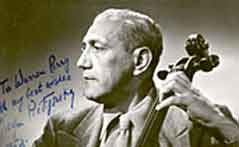

Gregor Piatigorsky

|

|

December 8, l929 I’ve been busy since I wrote last. And best of all, three weeks of the most enjoyable grand opera I can imagine. I suspect I’m infatuated with the prima donna. . . . Her name is Louise Caselotti, a local girl, nineteen years old, and a daughter of Maria Caselotti, prima donna of the Royal Opera House at Rome. Or maybe it’s the mother I’m infatuated with. The girl, slim and graceful, an excellent dancer, looks like a combination of Clara Bow and the Holy Virgin. Her voice is young yet. For dramatic effect, she creates her tones rather far back, making them a little dark and obscure. Vocally, there have been much better Carmens than she is today, but I seriously doubt if dramatically and in all those other things which Carmen demands more than voice, there has ever been a greater Carmen than she is right now. In the first place, her Carmen, utterly different from the usual voluptuous (pardon me) hussy, is a fiery little flapper of the year of Our Lord l929. In appearance, acting and dancing, she actually creates this new character as though Carmen had never been done before. There is nothing wild or unrestrained about her — in fact she shows considerably more restraint than is usual, yet there’s a blazing, suppressed fire about her which makes you want to hiss as you hissed the dirty villain in the ten-twent’-thirt’. . . . Then, too, the operas are being given in the Biltmore theater, which is small enough so that you can sit in the top gallery and toss an egg with unerring accuracy on the stage. There is a sort of Italian atmosphere — I’m not speaking of garlic. But if somebody wants to shout a brava during an aria, he does it, and if he wants to hiss, he hisses. The Cultured Iowans are in a minority, and the theater between acts has the atmosphere of the green room on first nights. Except for Caselotti, I’m not discovering any new stars. It’s the atmosphere and the ensemble. But now I must tell you of someone I have helped to discover. He’s a ‘cellist, named Gregor Piatigorsky, comparatively unknown in this country, I think. They call him the Russian Casals, but he’s the Russian Piatigorsky. There’s only one. Did you ever attend an orchestral rehearsal? As soon as the conductor lays down his baton, the musicians dash for the door and their lunch. Tuesday I happened to stop in just as rehearsal closed. Imagine my surprise when the conductor laid down his baton and the orchestra turned loose a flock of bravos and dashed, not for the door, but for the ‘cellist. It looked like the gang on the bench surrounding the fullback after he had run ninety-five yards to the winning touchdown. So I stuck around. They wouldn’t let that Bolshevik out of there until 2 o’clock, and there wasn’t a musician left the stage while he sat and played and played and played as Orpheus never played. The next day I snuck in the stage door and hid for another rehearsal, and the next day the musicians demanded and got another free recital. So you can imagine he’s good, regardless of what I might say. Remember the name and hear him when he goes to New York. As ever, Brick |